Mastering the Examination OSCE

OSCEs are notoriously challenging. You've memorised countless examination routines, rehearsed meticulously on your friends and spent hours examining patients on the wards. Yet, when the exam day arrives, something feels missing—particularly when you're faced with the daunting viva questions at the end of your station.

Sound familiar?

You're not alone. Many medical students excel at performing a polished clinical examination but struggle to articulate their findings clearly and confidently under examiner scrutiny. The solution? It's simpler—and more structured—than you might think: turn the exam on its head.

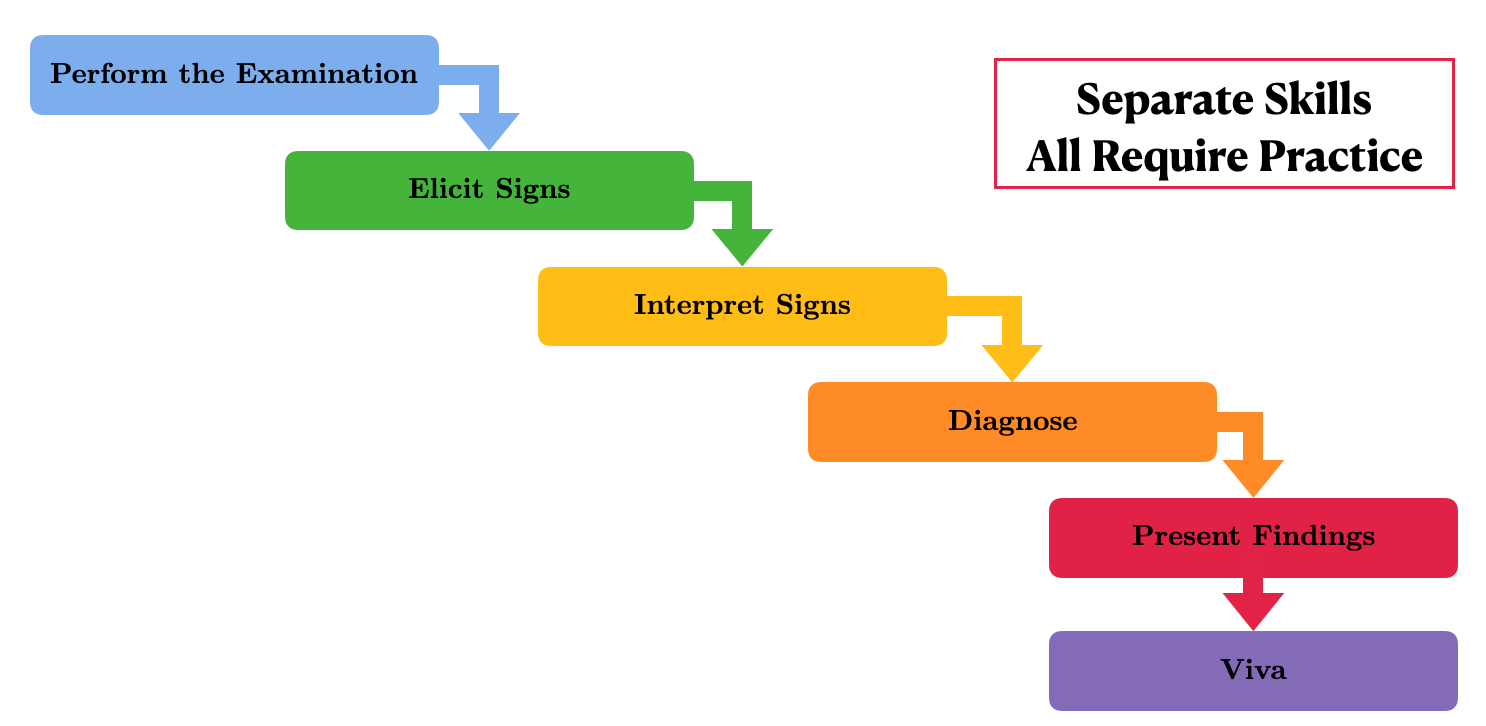

Traditionally, students start from the top, mastering examination routines first, and hope the presentation of findings falls into place. The retrospective approach I am about to share with you flips this entirely. It starts at the endpoint—the viva—and works backwards, ensuring you're always ready to clearly present and justify your clinical findings.

Speaking from the examiners' point of view, once the student has entered the room and met the patient, they tend to nod off once the candidate has started examining, after all, they have seen hundreds of others do this before. Unless the candidate does something really unusual, they probably won't be paying an awful lot of attention.

But then comes the presentation and the viva - this tends to be the part that really discriminates between candidates; did they pick up on the signs? How did they interpret them? Can they come to a sensible differential diagnosis? It is therefore this section where most of the points are scored.

The kicker is that most students neglect to practice the key skills required to succeed in this portion of the exam. I would argue that even once a candidate has picked up on the signs themselves, synthesising this into an organised presentation and forming a diagnosis is actually quite difficult.

All well and good, but how can one actually come up with a strategy to deal with these neglected OSCE components?

Here's how you can put this approach into practice:

First, start with a comprehensive list of high-yield OSCE cases for each examination type—think stable chronic conditions with clear, identifiable signs. "But wait," I hear you cry, "Surely this encompasses the whole of clinical medicine!"

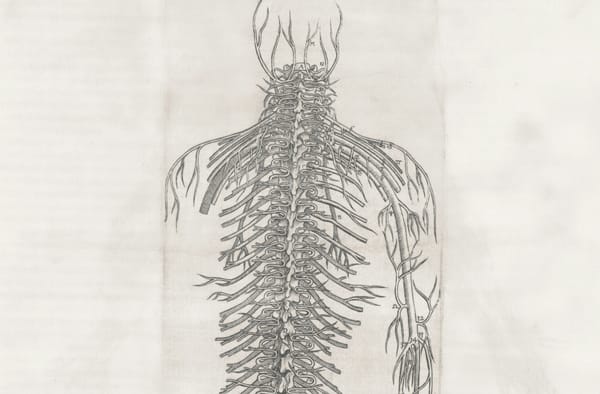

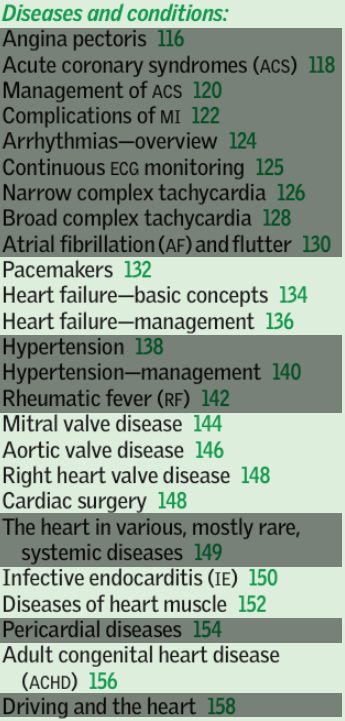

Actually, this is where the beauty of the OSCE comes into play. Whilst theoretically anything could come up, there's a much smaller portion of cases which are actually practical to bring to an exam. Taking cardiology as an exam, this is the contents page from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine (which I take as a good rule of thumb for the range of cardiology one might be expected to know for finals). The examiners want cases that are stable enough to sit through hundreds of medical students prodding them and have clear, reliable signs to make the exam fair.

Starting from the top, clearly they will not bring in a patient having an MI to the exam, so that's ischaemic heart disease out. Whilst AF is reasonable, it's only produces a single sign on clinical examination, so is not very interesting if an examiner really wants to discriminate between candidates. As with MIs, tachyarrhythmias are clearly not suitable for an OSCE because they have an annoying tendency to arrest. Pacemakers and heart failure are fair game, especially if there are associated signs as to why they are there. Hypertension alone is insufficient, and rheumatic fever is vanishingly rare in the UK nowadays (although someone with previous rheumatic fever could present with a valvular lesions). Now comes to the meaty segment - valve disease and cardiac surgery. Lovely stable signs. Infective endocarditis is possible, as are cardiac muscle disorders (e.g. cardiomyopathy). Pericarditis and cardiac tamponade are acute and obviously a no-no. Finally, adult congenital heart disease would also be a stable, chronic condition one could put in an OSCE. We have therefore weeded out over half of the cardiology content on these principles alone. The same can obviously be applied to other stations.

Next, instead of passively learning the steps of an examination, actively prepare your viva responses. For each condition, list positive findings you might expect to find and think carefully about relevant negatives. Imagine yourself in the exam hall: confidently stating your diagnosis, supporting it with observed signs and highlighting important negatives to strengthen your case.

A good presentation should therefore contain the following:

- The important positive findings

- The relevant negative findings

- What you think the diagnosis is

- How severe it is

- Minimal waffle

Imagine the busy post-take consultant - they want to know what you've seen, what you think it is and how urgently it needs treating. If you can do this, you demonstrate the higher-order thinking which they would want to see in doctors.

Practice speaking aloud. Take your set of positive findings and challenge yourself to formulate a unifying diagnosis on the spot. The real power of this method lies in your ability to clearly communicate your reasoning during the viva, not merely perform rote examinations. The examiner doesn't just want to see a smooth routine; they want to hear your clinical reasoning, your interpretation, and your management plan.

The 'typical' presentation I commonly see from students starts with the following:

"I examined Mr Smith who is…umm…75 years old. From the end of the bed he looked well. On inspection, there was no clubbing, no Osler nodes, no Janeway lesions. His pulse was regular, about 80bpm. There was no collapsing pulse…"

All very well, but the examiner has a mark sheet in front of them with a list of key signs they want to tick off. The better candidate will get to the point and construct a clear narrative leading the examiner logically to their conclusion.

Consider this structured presentation:

"On examination of this 70-year-old lady, she has a slow-rising pulse. There is an undisplaced heaving apex beat with an ejection systolic thrill over the right upper sternal edge. There is an ejection systolic murmur which radiates to the carotids and is loudest with the patient learning forwards in held expiration. I would like to check BP for a narrow pulse pressure. Importantly, the patient is not in heart failure and there are no stigmata of endocarditis. This patient has aortic stenosis, which appears to be severe due to an inaudible second heart sound and heaving apex."

Can you see the difference this makes? This is succinct and highlights all of the key points in the student's thought process that the examiner will want to see.

Some other pointers for when you practice this:

- Don't fiddle. This is distracting and quick annoying. Hold your stethoscope with both hands behind your back to stop you doing this.

- Avoid fillers "umm, like, sort of…". If you need to pause, just pause.

- Look the examiners in the eye, or there about. This is scary, so you can look at the point at the top of their nose between their eyes which gives the illusion of you staring them down. If there are two examiners, look in-between them and each will think you are looking at the other.

- Cut out the "on palpation…, on percussion…". The fact that you found an ejection systolic murmur implies that you auscultated it. These are just filler that wastes time.

How to practice this? Take your list of positive and negative findings for a given case and just have a go at presenting it to a friend, or even film yourself. You will see how challenging this is to get good, even when you have your 'script' in front of you!

The next step is to remove the diagnosis and practice being given a set of positive findings on the spot, presenting it and coming up with a diagnosis. If you head over to the 'Clinical Cases' section of the website, you'll find ready-made cases, each with clearly listed positive findings and structured viva questions. Practice presenting these aloud, refine your technique, and build confidence.

Other resources I would recommend are the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine Tutor Study Cards, which contain key cases in the very format I am talking about (diagnosis on one side, key signs on the other). There are lots of books available now for MRCP PACES, for example, Cases for PACES by Hoole et al, which do a lovely job of summarising all of the most commonly encountered clinical conditions and their associated findings.

Finally, how do I know this works? Anecdotally, I have taught my own students this methods who have gone on to do very well in their OSCEs - one even told me it was like a 'cheat code' for finals. I also discovered this gentleman who used virtually the same method and ended up coming top in the year at Cambridge:

In short, don't just prepare to examine—prepare to present.